The biggest difference between traditional Japanese tea cups and Western tea cups is that Japanese tea cups have no handle. There are two kinds of Japanese tea “cups” – yunomi, which are tall cylindrical cups, and chawan, wide bowls used to drink matcha in the Japanese tea ceremony. Unlike a chawan, a yunomi can be used for everyday tea drinking at your home or even at work. Japanese tea cups come in all kinds of styles and glazes, from white porcelain, to iron black, and unglazed clay. Like Western tea cups, however, there can be a huge range in prices for a single piece. A mass-produced factory yunomi are quite affordable, but a quality yunomi made by a master can cost over 10,000 yen.

When buying a Japanese tea cup, you should not only consider the style but also hold it in your hands and try imagine yourself drinking tea from it. The evolution of traditional Japanese tea cups can be traced through the Japanese pottery styles of yore—let’s examine the top five types.

Japanese Pottery Styles Explored

Raku Pottery

Raku has long been considered the top choice for chawan, the tea bowl used in the tea ceremony. This is because raku ware developed under the patronage of Sen no Rikyu, the founder of tea ceremony. Japanese pottery created in the true Raku mold is made exclusively by hand rather than by using a pottery wheel. Because of this and the special firing process used, every piece of Raku pottery is unique. There are two kinds of Raku – Black (kuro) and Red (aka) Raku.

Black Raku

Black Raku uses a glaze made from stones of the Kamogawa River in Kyoto. It is fired for a short time at a high temperature, then removed and allowed to cool outside the kiln. Exposure to oxygen while the pottery is still cooling creates the unique crackled texture and iridescence of Raku-ware; authentic Black Raku will always have an imprint left by the tongs used to remove it from the kiln.

Red Raku

Red Raku is fired at a lower temperature, but is coated with glaze and then re-fired many times. Raku uses various metals in its glazes, and acidic foods may cause them to leech. This is why Raku is usually only used as decoration or to drink matcha.

Satsuma Pottery

Japanese pottery made in the former Satsuma region of Japan (present day southern Kyushu) still bears the name of its birthplace. Early Satsuma pottery was originally made from dark clay and used plain styles. Later, ivory colored clay and a transparent, crackling glaze was used. In the 1800s pottery for export to Europe was in high demand, and Satsuma pottery style changed to match the tastes of wealthy Europeans. The new Satsuma pottery was ivory or cream in color, decorated in enamel or gilding with elaborate designs (such as saints, geisha, and dragons). However, the designs became over-complicated and quality decreased, causing Satsuma pottery to fall out of favor. Quality Satsuma ware, on the other hand, remains one of the most highly collectible pottery styles, still associated with traditional Japanese teacups today.

Bizen Pottery

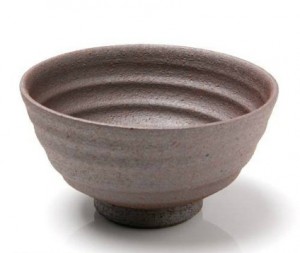

Bizen ware from Bizen, Okayama Prefecture is one of the oldest traditions of Japanese pottery. The reddish-brown clay is dug from the rice paddies in the Bizen area. Bizen pottery is unglazed when put in the kiln and is baked for 8-20 days in a pine wood fire. Because the fire must be kept going continuously during that time, firings often take place only a few times a year. The pine ash then gives the finished pottery a natural glaze, sometimes even producing a “sesame seed” spotting pattern. Modern day potters often try to recreate similar effects and shapes to the pottery produced in the late Muromachi and Momoyama periods, the heyday of Bizen pottery. Because this style is not glazed, the texture and color changes and improves through years of use. Bizen’s elegant simplicity has made it one of the most popular styles of pottery in Japan.

Shigaraki Pottery

Shigaraki pottery was developed in the town of Shigaraki, Shiga in the later Kamakura period (1192-1333). As one of the oldest Japanese pottery styles, it is part of the country’s “Great Six Kilns.” The first Shigaraki ceramics consisted of unassuming household pieces such as jars and grinding bowls. Glaze was not used, but the ash of the high-burning fire created a natural glaze effect. Later, the style became favored by the tea masters of the Muromachi and Momoyama periods and began to use some colored glazes. Shigaraki uses clay from Lake Biwa, which gives the pottery a warm orange tone. Air is allowed into the kiln during the firing process to create a unique effect through oxidization. Shigaraki has a natural, rustic look with a somewhat rough texture of speckled ash and minerals.

Imari Pottery

Named for the port from which the pottery was shipped, this style of Japanese pottery actually developed in the nearby town of Arita. Japan’s first ever porcelain was created around 1610 when Korean Yi Sam-Pyeong discovered the kaolin used to make porcelain inside an Arita mountain. Pottery techniques were much further developed in Korea than Japan, and so the foundations of Arita pottery (and Japan’s porcelain) were laid by Korean immigrants. Early Imari pottery thus imitated the white and blue designs of Korean pottery. Later, Imari pottery became popular in China and Europe, and specific styles were created to appeal to the tastes of both regions. In the 19th century, exports of Imari pottery surged to meet the demands of Japonism and the styles became more Westernized with bright enamel colors and gilding. The beautiful blue underglaze with red and gold designs was so popular that it was copied in Europe by famous kilns. Today, Imari pottery produced in Arita is still considered some of the finest porcelain in the world, existing not only as Japanese tea cups but also flasks, plates and other fine items.

Traditional Japanese Tea Cups: What determines Quality?

All of the above pottery traditions have culminated in the creation of high-quality Japanese tea cups—but what exactly sets them apart? Quality, traditional Japanese tea cups use the finest clay and glazes, and are uniquely created by hand by a master potter. Furthermore, while they almost never have handles, they are very comfortable to use. This is because Japanese potters carefully consider everything from the shape of the cup and how it will fit in your hand to the texture of the edge where it will touch your lips. Different Japanese pottery styles also have certain advantages; a white porcelain cup showcases the vivid colors of green tea, while a stoneware or earthenware cup (fired at a lower temperature) will absorb the flavor and color of tea over time to create a richer tea-drinking experience. Porcelain and unglazed cups are also hotter to the touch than those with a thick glaze.

If you would like to add any of the Japanese-style tea cups mentioned here to your collection, click on the links above for authentic products direct FROM JAPAN.